Fairy Tales is an itinerant exhibition about the construction and deconstruction of stories, myths and legends regarding identity and legacy. It traces the constant falling apart and re-emerging of stories we tell ourselves in order to survive. In hindsight, these necessary illusions often seem like fairy tales but they are far from neutral as they have had, have and will have a real impact in the construction of the self and societies. The understanding of reality is largely determined by our shared cultural horizon which manifests itself in many forms —that of language, imagery, religion or politics, among others — leading in most cases to the creation of a fiction that allow us to cope with the complexity of existence.

Curiously, the word person has its etymological roots in the Ancient Greek term prósopon that referred to the masks used by actors in theatre (pros = in front of and opos = face). In Latin, the equivalent word slightly shifted to persona which phonetically mirrors the wording per-sonare, or what is the same, to make or amplify sound. It turns out that the term that perhaps most emphatically encapsulates the modern idea of individuality, borrows its meaning from an ancient device used by actors to perform. Such a semantic pirouette somehow negates, or at least puts pressure, on widely socially accepted ideas such as the individual perception of the self. Under this light, the word person becomes somewhat a little bit more elusive and ambiguous, lessening core ideas such as the individual quest for authenticity, the construction of a unique personality and so on.

The same could be said about the notion of the Western modern state. Artificially manufactured throughout the course of the nineteenth century, newly formed parliamentary states made a conscious effort to produce a common cultural, social and political horizon with the aim of generating a shared identity with a strong sense of belonging among a disparate range of peoples and regions. The establishment of such a collective horizon allowed states to produce a fiction (an illusion, a narrative) that almost in no time the great majority eagerly adopted as their own. By looking back to folklore, customs, arts and crafts, as well as certain historical figures, states could both amalgamate communities, and more importantly, were able to trigger an emotional response that later lead to nationalistic effervescence.

Myths and religions have also been quite effective ways to fill in the gaps of our limited understanding of reality. By telling (or singing) understandable and relatable tales about the ungraspable mysteries of existence, societies and individuals have been able to cope with the unknown and carry on with their own lives. Reducing the ever complex realm of existence to human-like riddles or fables, have conformed a collective form of consciousness that conformably brings such fears at ease. And the list could go on, from the illusion of of time as a linear arrow that relentlessly moves in one direction or the understanding of reality as cause and effect, to the logic of late capitalism and technological advance that narrows to only a few the variables that structure our daily lives. The use of models, formulas and protocols create an illusionary sense of control and set in place ready-made recognisable frameworks that allows societies and individuals to live on.

The artworks on view use the framework of the fairy tale —or constructed narratives— to examine and question some of the gloomier aspects of our human condition. By creating alternative pasts, using displacement, and reciting existing conditions in unexpected ways, the artists turn reality into an entanglement of abstraction and desire. The artists in the show explore this tension through a variety of medium-specific perspectives that lead them to tackle a wide variety of issues from politics, migration and economics to architecture, history or science. This heterogeneity of approaches brings to mind what curator and researcher Chus Martínez wrote in her essay Clandestine Happiness: What Do We Mean by Artistic Research? (Index, 2010), when she introduces the idea of artistic research understood as an effort to understand reality by connecting disparate ideas systems and knowledges that would otherwise never intersect. Fairy Tales is a show where artists speculate productively in order to subvert existing narratives, dream of alternative futures and find a sense of agency.

photos : Grimalt de Blanch

“Fairy Tales” is an exhibition focusing on the construction and deconstruction of stories, myths and legends regarding identity, history and legacy. This exhibition uses the framework of “fairy tales” to examine and question our human condition. The included works imply an imminent end of something which used to exist, without imposing a solution or an alternative future. They aim to shift your gaze from the often-uncomfortable relationship between people and their environment to a different perspective. This shift enables creating alternative histories and retelling the existing ones in unexpected ways. Thus a new fairy tale begins; the modern-day ones that we need to believe in order to survive.

And, A Way of Reading 《Fairy Tales》

Chapter 1 – A Certain Crisis

In an era where we are inundated with « stories » some argue that narrative itself is facing a crisis. Consider this: if you were to take photos of an exhibition currently unfolding before your eyes and share them in real time on social media, the content distributed would appear to be in the form of a « story. » Yet, it ultimately exists as information consumed instantaneously. What is missing here is true narrative—stories with their own context, their own life. Is it possible, then, to tell stories that, instead of endlessly seeking and displaying new information, allow us to dream and view different modes of life, perception, and reality from a distance? Could a community emerge that listens to such stories?

This exhibition, titled « Fairy Tales » which evokes the genre of tales populated by fantastical beings, gathers the works of eight artists from South Korea and abroad to explore the potential of storytelling in a time when narrative seems to be under threat. Starting in 2023 in Antwerp, Belgium, and moving through Seoul, Tokyo and Mallorca, this touring exhibition is led by five core artists and curators, yet it also invites new artists to participate depending on the venue and location, fostering a polyvocality and variation in narrative. As the curatorial team explains, “Fairy Tales” is a long-term project that « tracks the process of the stories we tell ourselves continuously collapsing and re-emerging » borrowing the structure of fairy tales based on fantasy to reveal the light and shadow of society. The works included in the exhibition share a common approach of using the conjunction ‘and’ to link “Objects and events that are originally unrelated, trivial, meaningless, or auxiliary, into stories that seem to transcend raw reality.” Objects and time, once isolated, are thus reconnected as a force to reawaken our perception of alternatives and reality within these narratives. Moreover, the conjugative ‘and’ becomes a valid method for reading the exhibition itself. Instead of confronting the disparate works of Carla Arocha & Stéphane Schraenen (VE,BE), Marc Ming Chang (FR/CN), Jaehoon Park (KR), Jesse Siegel (MX/US), Jan Tomza Osiecki (PL), Vanessa Van Obberghen (BE/KR), Luc Tuymans (BE), and La Kim (KR) within a fixed order or linear structure, the audience is invited to connect them according to their own perspective and build a narrative. Likewise, this preface can be continuously fragmented and recombined to make another story possible.

Chapter 2 – Distortion and Ambiguity

As you walk towards the exhibition space, the first work you encounter from the outside of the building is Carla Arocha & Stéphane Schraenen’s Twilight Zone, a piece that materializes the fantastical aspect of fairy tales through architectural intervention. The duo, who have been collaborating since their 2004 project at Kunsthalle Bern, continuously reinterpret the visual lexicons of 20th-century European and Latin American abstract art, minimalism, and op art. They often create installations that respond to or intervene in specific sites. At WWNN, they attached a material to the gallery’s glass windows that generates a moiré effect, transforming the exhibition space into one filled with “glittering mist, dazzling smoke, and silvery clouds.” The interference patterns on the glass surface distort the gaze and light that penetrate through the gallery from the outside, setting the exhibition as a transitional “twilight zone” as the title suggests. In this space, both the audience and the artworks experience possibilities of transformation, change, and mutation.

Distortion plays a crucial role in Jan Tomza-Osiecki’s sculptural series Thirst #1 and Thirst with Tentacles as well. The two eye-catching, smooth purple sculptures are made of Galalith, a type of plastic produced from the interaction of milk protein, fish scales, natural pigments, and formaldehyde. Known for its extreme porosity and tendency to warp, this material led to the bankruptcy of all companies that attempted to manufacture it. The artist not only allows but encourages the plastic to warp and bend itself, thereby amplifying the material’s inherent imperfection. Unlike “today’s dull polymer plastics” the Galalith sculptures occupy space as non-human objects that thirst and desire, silently exploring their surroundings with tentacles or protrusions extending from their bodies.

Jesse Siegel, who has long been engaged in merging and translating memory and record, often draws conceptual and formal motifs from ‘new towns’ like Cancun, Mexico, where he grew up. In Flourish (Cancun), part of a series he refers to as “memory photographs,” the artist captures metal bars while walking through Cancun’s “old town” just fifty years old, and digitally reprocesses these images. These architectural elements, called Barrotes in Spanish, often function as ornate and elegant architectural adornments, but the same word also refers to prison bars, indicating their role as defensive mechanisms. Focusing on the duality of these visually beautiful grills, the artist photographs, edits, and outputs them through 3D rendering, attempting a media translation process. This process appeals to deeply embedded memories within the artist—memories that are gradually forgotten and distorted—by gradually removing the materiality of the subjects recorded in the photographs, decontextualizing them, and offering opportunities for new stories to be written.

Belgian painter Luc Tuymans also focuses on the imperfection of memory through painting. Often using diffused colors, the boundaries between color and form in his work are intentionally blurred. Although he does not explicitly reveal his subjects, his paintings, which subtly depict everyday scenes, are grounded in a specific interest in violence. Thus, the “information” he encounters daily through films, advertisements, and news becomes a crucial clue and motif, reprocessed into imperfect memories. Peach and Technicolor, based on an advertisement film from 1913, is an image recreated using acrylic ink on tracing paper and assembled into a short animation of about three seconds. In the process of transitioning from lens-based media to painting and then to time-based media, the « peach » loses its original intended meaning as a consumable product and advertisement object. Similarly, the blue flower in Seconds II, completed using the same method, also reveals only an amplified ambiguity, devoid of specific meaning, value, or symbolism.

Chapter 3 – Life and Reality

Some of the artists participating in Fairy Tales sharply illuminate the violence and melancholy inherent in reality through fictional settings or autobiographical narratives. Marc Ming Chan, known for his miniature drawings, captures the history of human conflict and catastrophe in a poetic manner in his Smother series, introduced in this exhibition as monotype prints overlaid with pencil drawings. The drawings, demanding close observation, evoke numerous destructive accidents and disasters that have spread through news, from the fire at Notre-Dame Cathedral and volcanic eruptions to massive wildfires worldwide, the Kuwait oil field fires, and the 9/11 attacks. Yet, they also intersect with the artist’s intensely personal experiences. He confesses that Smother metaphorically represents the conflict between parents and children that has persisted through generations. The dense smoke, filling the small surface and imbued with tears and water spray, remembers his mother’s death in 2021, contemplating the (im)possibility of mending relationships.

Vanessa Van Obberghen, born in Daegu, adopted overseas, and raised in Kigali before studying in Belgium, also draws on her own life as the primary subject of her work. Continuously exploring the role of « documents » and the misunderstandings that arise when information is translated, she deals with the concepts of restitution and return by juxtaposing the process of reclaiming her lost Korean citizenship with the history of Korean independence in her new work Bokwi. The plates in the “perpetually incomplete” drawing book offer an opportunity to translate and restore the artist’s personal history and life, including illustrations of traditional Korean chaekgeori paintings filled with the artist’s personal belongings, and images of her name written in Braille. The accompanying two-channel video Present Perfect critically addresses the impact of the past on the present, through scenes of non-European high school girls reciting Latin texts.

In contrast, La Kim reconfigures the relationship between identity and reality into a discourse on the digital and corporeality. She has been absorbed in separating, recombining, and giving dimensionality to images produced by photographing real people or plants with hand-drawn and hand-crafted models. According to the artist, the hybrid collage method, which encompasses both analog reality and digital virtuality, is significant because “hidden stories are discovered in the virtual space into which reality is drawn.” In his B series, referring to Box, she collaborates with practitioners of jiu-jitsu, mountaineers, and contemporary dancers, focusing on the uncertain reality of the body due to the rise of digital programs, and explores the world of transformation symbolized by the boxed space.

Jaehoon Park, who works between Amsterdam and Seoul, more actively utilizes 3D simulation in virtual digital spaces to suggest that our lives are filled with contradictions, like a theater stage. His video world, constructed from a wide array of sources, including ready-made 3D models uploaded to the internet for game developers, drone footage archives, and 3D scan data extracted from photogrammetry, reflects humanity’s impact on the Earth’s ecosystem through « hyper-capitalism » and endless desire. In his works, mass-produced objects appear “in a hellishly desolate digital space” or emerge as virtual ritual installations. As exemplified by Guillotine Room, which portrays a scene of solar execution in the galaxy with a guillotine—a device designed for efficient execution—at the center, the fairy-tale fantasy and fiction do not embellish reality but rather expose its contradictions in a raw, unfiltered manner.

In a time when speculative possibilities in fables, tales, and narratives are being actively discussed, the artists contributing to Fairy Tales provide not an escape from reality, but a chance to examine it with greater precision and honesty. In this context, the works temporarily inhabiting the exhibition space invite us, as viewers, to engage not with mere information, but with stories-imaginative fictions that mirror and deepen our understanding of the real world.

Sooyoung Leam (Independent Curator, Art Historian)

1- Byung-Chul Han, translated by Ji-Soo Choi, The Crisis of Narrative (Dasan Books, 2023)

2- Unpublished exhibition portfolio.

3- The Crisis of Narrative, p.61.

4- Rod Serling, The Twilight Zone, black-and-white mystery TV drama, late 1950s

Intitulée “ELLIPSIS”, cette exposition réunit trois artistes majeurs de la scène européenne s’attachant tout à la fois à l’introspection et à l’influence du corps social. La diversité des supports et des techniques que chacun utilise est portée par une même volonté à sonder l’âme humaine et son empreinte dans le monde contemporain. Le thème confluent navigue donc entre l’intérieur et l’extérieur, en jouant de l’ellipse, procédé littéraire ou cinématographique qui consiste à faire abstraction d’un ou plusieurs éléments d’un récit, sans pour autant en affecter la compréhension. Le contexte d’exposition donne donc au visiteur le rétablissement de cette omission.

Ces dernières années, Marc Ming Chan a choisi comme thème de recherche le “confinement spatio-moral” : situations d’isolement et de méditation qu’il exprime selon des formes énigmatiques et paradoxales. Ses œuvres récentes, peintes à l’acrylique, s’apparentent ainsi à des constructions sculptées : stèles, parois futuristes, labyrinthes de vestiges imaginaires. Pour “ELLIPSIS”, l’artiste expose la série inédite de dessins “Smother”, au crayon Posca noir avec rehaut blanc sur encre de Chine délavée, qui s’attache à des fumées sombres, conséquences de catastrophes et des conflits actuels. Il présente également plusieurs sculptures-boîtes de la série “Hippocampus” pour laquelle des compositions graphiques de couleur cuivre et bronze viennent souligner des assemblages en bois évoquant des ruines constructivistes. Enfin, la série “Bone” développe des cellules reliées par un passage, espaces théoriques et mentaux sublimés par des teintes spectrales irisées sur fond noir texturé. Leurs supports sont découpés selon le contour de la composition. Ce motif de chambres reliées, récurrent dans les travaux de l’artiste, révèle son approche de la cellule comme lieu sécurisant, avec pour background le vide stellaire, allégorie de la nocivité.

Ce catalogue a été réalisé à l’occasion de l’exposition GROUND CONTROL, organisée du 24 novembre 2023 au 11 janvier 2024.

Commissaire de l’exposition : Marc Donnadieu, en étroite collaboration avec Clara Djian et Nicolas Leto.

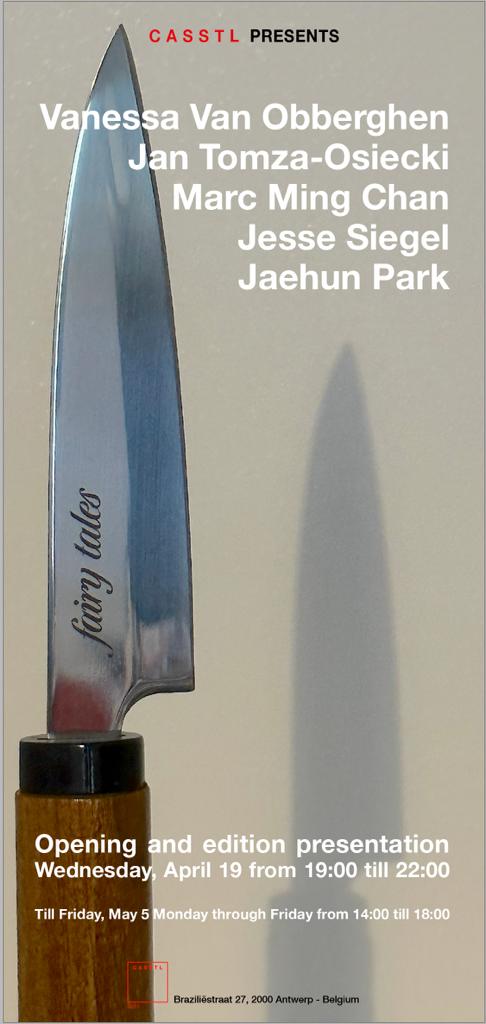

EXPOSITION FAIRY TALES – CASSTL – ANTWERP

BLINDAGE 231 et BLINDAGE 232

Les deux œuvres de la série “Blindage”, présentée dans le cadre de l’exposition “Fairy Tales” chez CASSTL à Anvers (Belgique), s’inscrivent au cœur des origines les plus profondes de cette série. Leurs images quasi subconscientes renvoient aux contes de fées racontés aux enfants afin de stimuler leur imaginaire, ou que l’on se raconte adulte afin de mieux contrôler son comportement ou ses émotions. Plus les ressources intérieures sont importantes, plus forte sera dès lors la capacité d’adaptation ultérieure. Pour le survivant du futur, se laisser tomber dans le trou afin de suivre la course du lapin d’Alice est une forme envisageable de chute salutaire.

Les soldats – ou les chasseurs dans les mythes, les contes et les légendes – symbolisent la protection. Le détenteur d’armes domine et contrôle, et par conséquence rassure, telle la présence parentale. Dès que celle-ci se révèle défaillante aux yeux de l’enfant, cette présence symbolique parallèle est d’autant plus indispensable face à ses besoins permanents à se sentir protéger et en sécurité. Ici idéalisé à travers l’iconographique militaire, ce phénomène vital de protection et son principe de construction mentale reflètent une nécessité primaire lors des premières années de l’enfant – et ensuite pour l’adulte au fil de sa vie – à entrer, à se former et à s’entrainer à survivre dans un monde perpétuellement hostile. Et cela en raison des difficultés inhérentes à chacun en matière d’identité, de socialisation, de communication vis-à-vis d’une barbarie latente ou d’un déclin cognitif.

Les structures mécaniques autour des deux personnages fonctionnent comme des boucliers. Ils sont élaborés à partir d’éléments de tanks, de réacteurs ou de fuselages aéronautiques. Leur représentation dure et solide – quoique chaotique et déstructurée – résonne ici comme une construction subconsciente. Imparfaite et transitoire, l’illusion ne fonctionnera que jusqu’à la prochaine mise à jour.

L’ensemble personnages + structures mécaniques opère comme la pratique de bodybuilding, hypertrophie après hypertrophie, à l’instar de la fin tragique de Tetsuo dans Akira. La course à l’augmentation de nos propres capacités ou l’acquisition de nouvelles options performantes reflète notre désir permanent de séduction et d’acceptation, d’abord envers nos parents, ensuite dans le cadre du monde du travail et du réseau relationnel – forme de déclaration de guerre intérieure dont les deux pôles antagonistes sont la quête de reconnaissance et son insatisfaction inéluctable.

L’aspect spectral du traitement pictural des œuvres interroge, lui, la tangibilité du sujet. Les rendus métalliques apparaissent et s’évanouissent, mimant ainsi l’effacement et la disparition de la seule force de l’enfant : l’innocence.

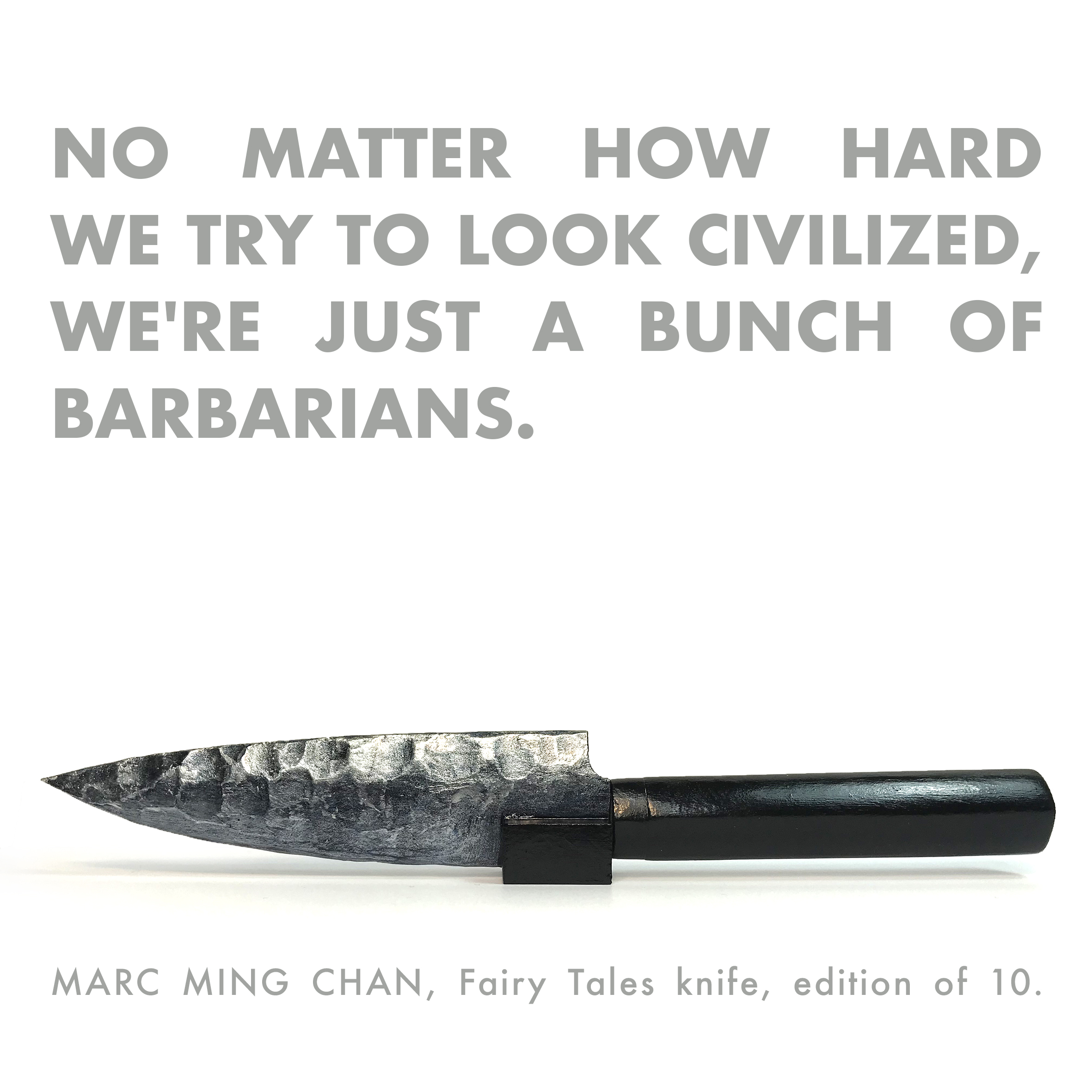

FAIRY TALES – LE COUTEAU DE MARC MING CHAN

Le fourreau en bois du couteau de Marc Ming Chan pour l’exposition Fairy Tales est taillé comme un silex, à l’instar d’un appel à nos ancêtres. Il instaure dès lors un dialogue entre le primitif et le civilisé.

À l’époque du Néandertal, le couteau de silex est l’un des premiers outils taillés de l’humanité. Il est, ensuite, l’un des rares objets sociaux parfaitement ambivalents : présent pacifiquement dans nos foyers, au moment des repas entre amis ou en famille, ou plus cruellement lors d’une attaque ou d’un crime.

Un socle le maintien en équilibre, côté tranchant vers le ciel, telle une offrande des contradictions humaines aux dieux.

Dans son packaging, il est accompagné d’un ruban de papier avec la phrase “No matter how hard we try to look civilized, we’re just a bunch of barbarians”.

Comme tous les couteaux des 5 artistes de Fairy Tales, sa lame d’acier, de fabrication japonaise, est gravée du titre de l’exposition.

Chaque projet de couteau est édité à 10 exemplaires.

Fairy Tales – CASSTL, Braziliëstraat 27, 2000 Antwerpen.

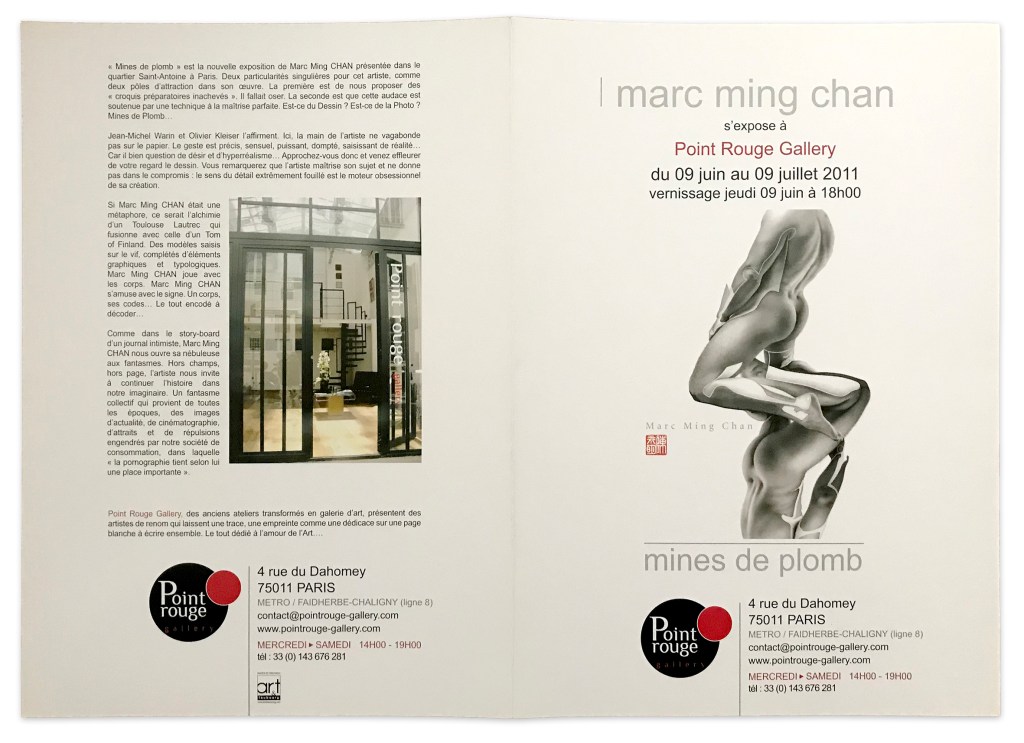

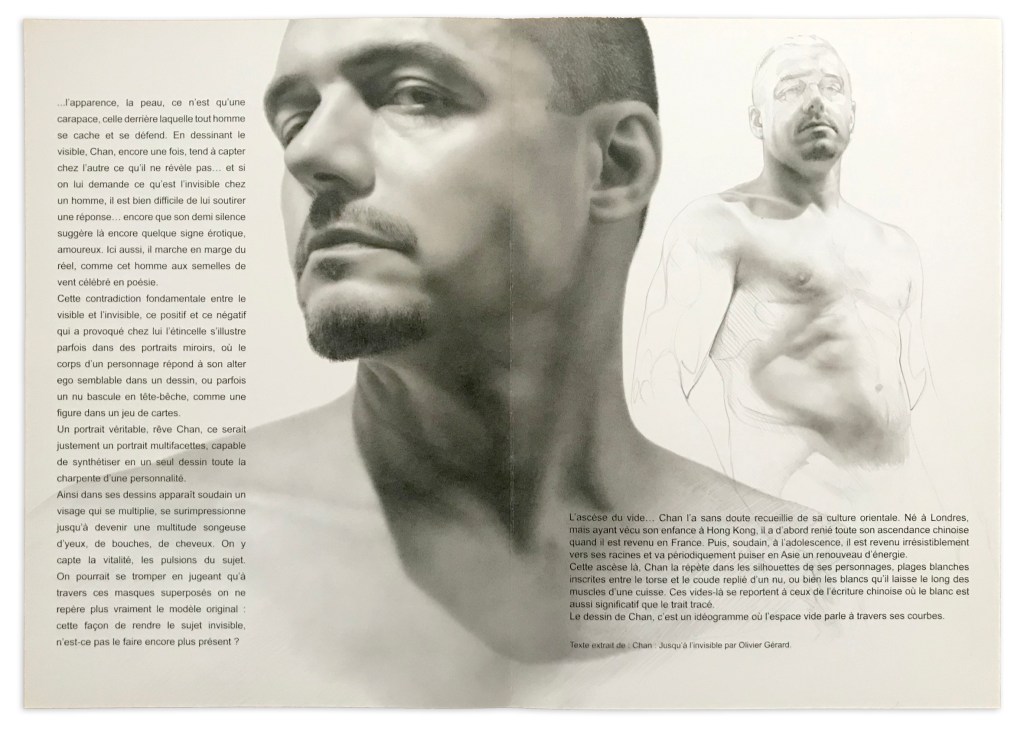

Jusqu’à l’invisible, par Olivier Gérard.

Tandis que dans la réalité, par le trait, la touche, la courbe ou l’estompe son regard aigu, ses mains éloquentes envahissent un papier que la blancheur défend, Chan, au fond de lui-même, tel le piéton de l’espace progressant d’une marche impalpable dans le cosmos, avance à pas mesurés dans son exploration de l’invisible. C’est bien ce qu’il cherche, Chan : plus il dessine, plus son crayon s’active, plus les formes naissent sur sa page, et plus il progresse dans sa quête de ce qui est au delà de l’image – sa quête pour traquer le vide. Pas le vide du néant, ni celui qui refuse la vie : un vide qui enjambe les apparences, se met à parler quand le graphisme se tait, un vide puissant et riche impossible, suggère-t-il, à traduire autrement que par la blancheur.

Est-ce pour atteindre cet objectif qu’il dessine ? Il a pioché au cours de son enfance dans l’atelier et l’arsenal pictural de ses parents pour y trouver les instruments de sa vocation : le crayon, le pinceau, les couleurs . Il aurait tout aussi bien pu devenir musicien ou peintre. Mais non, son âme, c’est le dessin. Un dessin auquel il donne des frontières très précises, ce qui ne veut pas dire limitées, car plus le champ est étroit, plus le contenu est dense.

Dès qu’on l’aborde, il nous plonge de le monde du graphisme, lui qui est adepte du tatouage et qui en a fait sur son propre corps le florilège, puisant dans la tradition de l’irezumi japonais, des samouraïs ou des yakuzas. Offrir le satin vierge de sa peau à la pointe de l’aiguille, se créer une seconde peau, c’est déjà une démarche tellement voisine de l’art de jeter des formes sur cette autre peau : le papier !

(…)

Chan : Jusqu’à l’invisible. Texte intégral ici.

Chan: Pencilled invisible. English version here.

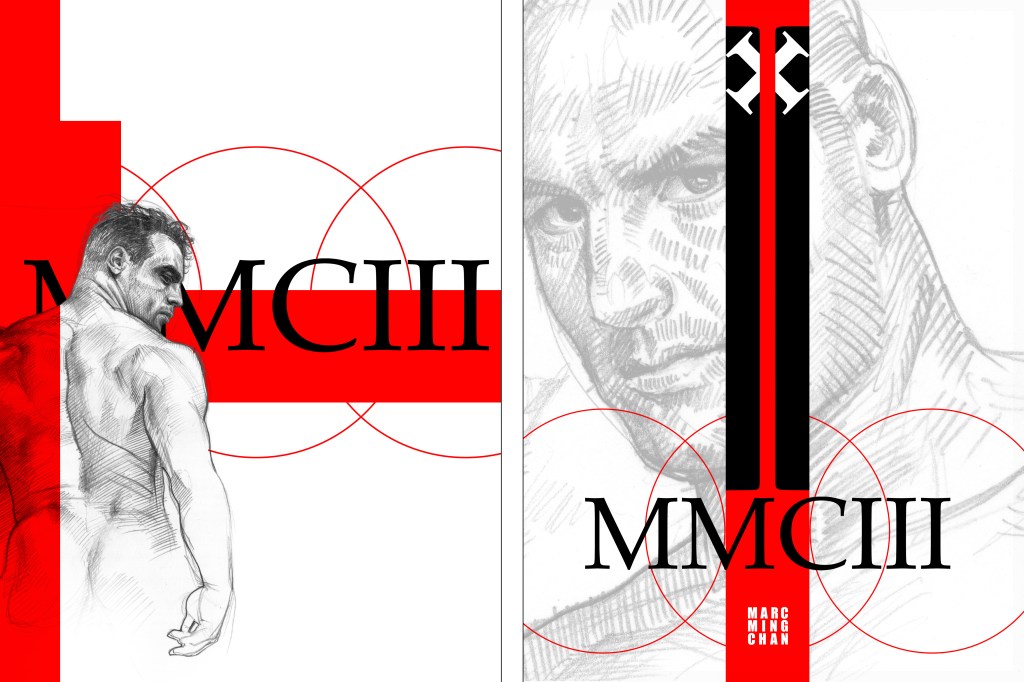

Je vous jouis, par Charles-Arthur Boyer. Préface de l’album MMCIII.

« Écrire, c’est se révéler tel qu’on est pas

pour qu’enfin on puisse vous comprendre. »

Mathieu Lindon

« Les œuvres d’art naissent toujours

de ce qui a affronté le danger, de ce qui est allé

jusqu’au bout de l’expérience, jusqu’au point

que nul humain ne peut dépasser. Plus loin on pousse,

et plus personnelle, plus unique, devient une vie »

Rilke

Ainsi que le souligne Mathieu Lindon dans son dernier livre, “Je vous écris”, Hervé Guibert conclut “L’Image fantôme” par cette injonction : « il faut que les secrets circulent… » ; et la vie, la littérature, la photographie comme lieu même de cette circulation dévoilée des secrets, et d’une circulation plus générale des mots et des images. Dès lors dans sa vie, dans ses livres, dans ses images, les secrets vont se découvrir – dans le texte –, et être découverts – par le lecteur –, sans aucune retenue. Aussi, ne seront-ils plus “bien gardés” mais “regardés”. Aussi, seront-ils “livrés” (parfois en pâture et avec insolence) autant que “délivrés”. Pourquoi ? Parce que justement la vie, le monde, circulent peu – et certainement pas assez – dans les textes et les images aujourd’hui ; la vie avec tout ce qu’elle charrie pour un homme – fut-il journaliste, écrivain, photographe – de plaisirs, de désirs, de jouissances, de souffrances ou de défaites. Et quand plus rien de vivant ne circule dans la représentation, se “forment des fantômes” qui viennent hanter le territoire du réel comme celui de nos propres existences.

Il en est souvent de même dans le travail de Marc Ming Chan, travail qui a pris tour à tour la forme de livres, d’affiches, de cartes postales, d’illustrations pour magazines, d’œuvres exposées dans des bars, des magasins ou des galeries d’arts françaises, américaines ou hollandaises. Mais de ces lieux et de ces objets de circulations multiples et différenciées s’il en fallait, nous n’en avons pas encore dévoilés la teneur. En effet, il s’agit le plus souvent de dessins au crayon noir, de facture classique, parfois accompagnés de mots ou de textes, dont le sujet central pourrait se définir ainsi : les pratiques sexuelles des homosexuels aujourd’hui. Peu importe, comme dans un livre, comme dans une photographie, si tout cela est une réalité ou une fiction, un reportage ou une mise en scène, un tissu d’expériences accumulées ou une interprétation, tout cela parle et fait image, tout cela nous parle et se révèle à nos yeux non comme une vérité mais comme un dicible, un possible, un en-visageable. En quoi est-ce important dans un monde que l’on dit si permissif et que par trop traversé d’images sexualisées à l’extrême ? Justement par que ces dernières images ne re-présentent rien et ne nous re-présentent en rien, Elles ne sont que des couches ou des effets de surfaces lisses, propres et policées. Elles ne prennent ni la parole, ni ne donnent de visage à l’autre, ni ne re-donnent quelque chose au visible. Rien de la vie ou du monde n’y circule. En revanche, fondé sur cette technique particulière du dessin qui point par point, trait par trait, tire la figure du néant du blanc de la feuille de papier pour que le sujet accède à une re-présentation – néant où elle pourrait, presque à tout moment, retourner –, le travail de Marc Ming Chan d’une part, et ce n’est pas la moins importante, livre de l’homosexualité une réalité vivante, active, sexuée qui, il n’y a pas si longtemps que ça, était encore clandestine. Et, dès lors, la délivre de ses “voiles”, de ses “gardes”, de ses “fantômes” – sinon de ses “secrets” –, en lui donnant une parole, un visage, explicite et sans compromis. Mais il y fait surtout circuler du souffle, du sang, des cris, des larmes, de la salive, de la sueur et du sperme ; autrement dit, les aspérités du corps, du désir, du plaisir y font prises, les fluides s’y déversent, la jouissance ou la souffrance y font saillies.

(…)

Je vous jouis. Texte intégral ici.

Chan: I cum you. English version here.

Entretien avec Guillaume Dustan.

Novembre 2003.

Bonsoir.

Est-ce qu’on peut commencer par une espèce de vague bio, ou pas ?

Ouais.

Ben en fait, euh, moi ce qui m’intéresserait surtout ce serait, quelle est ta formation euh, artistique, quoi ?

Bon, brièvement, j’ai commencé vers l’âge de seize ans à faire mes premières peintures, avec pas mal de facilités parce que mon père était artiste-peintre, donc on avait à la maison, ma mère vendait des articles de peinture, pinceaux, couleurs et toiles étaient à disposition, tout ça était un peu étalé dans le temps, j’ai arrêté, j’ai fait d’autres choses, et puis, quand j’ai eu dix-sept ans, je voulais bouger de Charleville, donc j’ai fait l’école Duperré, les arts appliqués, j’ai appris pas mal de choses, bon, je n’ai pas été jusqu’au bout, parce que c’était assez contraignant, on était un peu dans un moule, et ça ne me correspondait pas trop.

C’est quoi l’école Duperré, au juste ?

C’est une école d’arts appliqués, on a deux premières années où on touche un peu à tout, peinture, sculpture, photo, film, on se spécialise après. Bon, j’ai dessiné par-ci par-là, soit tout seul, soit avec des modèles, j’ai vécu une vie d’artiste pas inintéressante ; à partir de 95-96 j’ai commencé à dessiner des choses sous le nom de Fury 161, donc là ça a commencé à se préciser.

T’avais quel âge quand Fury est né ?

Vingt-neuf. Vingt-huit, vingt-neuf.

Et donc t’as fait des dessins pendant des années, du nu, du nu, du nu, et tout ça.

Ouais, du nu et beaucoup de portrait, je m’inspire beaucoup de la peinture de la Renaissance, du portrait classique, des personnages très posés, imposants, rassurants.

C’est qui alors, les influences revendiquées ?

Rembrandt. J’aime beaucoup Ingres, il y en un que j’aime beaucoup aussi, c’est Gian-Battista Moroni, oui, c’est vraiment celui que je préfère, même si je connais peu de choses de lui, dans les moins classiques, il y a aussi Bacon, bien sûr, même si ça ne se retrouve pas dans mon travail directement, il y a aussi beaucoup de photographes contemporains aussi.